In April of last year, a freelance photojournalist named J.D. Duggan was covering a protest in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, a suburb of Minneapolis, when things took a disturbing turn. A few days earlier, a police officer in Brooklyn Center had shot and killed 20 year-old Daunte Wright, and a community wounded and incensed by George Floyd’s murder less than a year earlier took to the streets.

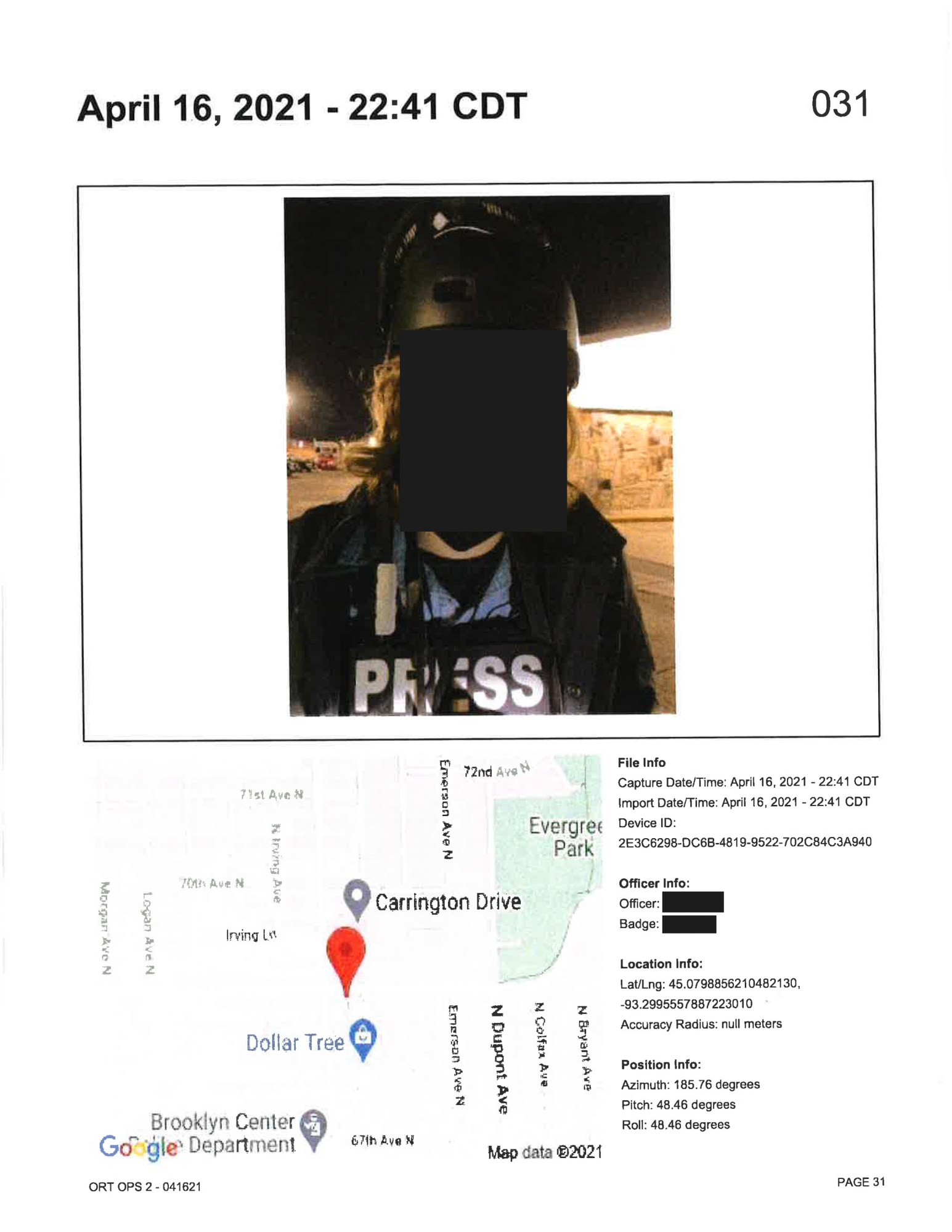

As Duggan was documenting the demonstrations, they say a “couple hundred” officers surrounded a group of protestors and journalists and told everyone to get on the ground. Officers sorted the press from the protestors, walked them to a parking lot, and began photographing them, one by one, with cell phones. Duggan estimates that a few dozen journalists were cataloged in the same manner that night before being released.

“I asked where the pictures would go,” Duggan says. “And the officer told me that it just goes into their system. He didn’t really give me any details. He said they have an app.”

Duggan filed a personal data request with the Minnesota State Patrol on April 17. On July 19, the state patrol provided three pages that included multiple photos of them, the geographical coordinates of where the photos were taken, the angle of the camera, and information about the officer using the application. MIT Technology Review requested the rest of the document in which Duggan’s personal data appeared on January 21, 2022, as well as information about the collection, retention, and dissemination of Duggan’s information. The state patrol disclosed that the data was collected using a tool called Intrepid Response, which appended geolocation data to the images. Another journalist who was photographed that night, Dominick Sokotoff, also obtained his personal data from the state patrol. It appears to have been collected and stored in the same way as Duggan’s.

Intrepid Response, a product of Intrepid Networks, provides an easy means to capture and share information that identifies whoever is on the other side of an officer’s smartphone. The app was critical to the law enforcement agencies that assembled and analyzed information about people at the Brooklyn Center protests, allowing them to almost instantly de-anonymize attendees and keep tabs on their movements.

The photos and data shared in real time via the app found their way into one of three known data repositories that MIT Technology Review has identified which include photos and personal information about individuals at protests and appear to be accessible to multiple agencies, including federal groups. None of the other journalists who were photographed while covering the protests appeared to have been charged with any crimes or told they were suspects while their data was being collected.

Policing agencies in Minnesota compiled the shared documents, spreadsheets, and other databases as part of Operation Safety Net (OSN), a multiagency effort to respond to protests stemming from George Floyd’s murder that has expanded far beyond its original publicly stated scope and appears to be ongoing.

To support MIT Technology Review’s journalism, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Several agencies involved with OSN have access to Intrepid Response, including the Minnesota State Patrol, the state’s Department of Natural Resources, and the Minnesota Fusion Center, according to the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. Fusion centers are controversial data sharing centers that analyze and disseminate information across local and federal law enforcement agencies, the National Guard, and others. Intrepid Networks’ website reports that the Saint Paul Police Department uses the Intrepid Response software, and the company’s marketing materials feature a testimonial from the department’s assistant chief of police commenting on the role of the app during last year’s unrest. It’s likely that federal agencies were also able to access information collected via Intrepid Response and shared with the Minnesota Fusion Center.

Like Slack for SWAT

Sold by AT&T, Verizon, and others, Intrepid Response is a communication platform that offers “a geospatial solution with feature-rich live mapping” and the ability to “view all personnel, tagged assets and map markers in near real-time,” according to the Intrepid Networks’ website. Marketing materials boast that “next-generation situational awareness makes the Intrepid Response for FirstNet platform the ultimate resource for tactical coordination and front-line intelligence.” The application, which can be downloaded like any other smartphone app, offers real-time data sharing, a platform for coordination of multi-agency teams, “highly secure team communications” (including push-to-talk and instant messaging), and more.

Britt Kane, chief executive officer of Intrepid Networks, says the tool is designed to increase transparency, decrease response time, and ultimately save lives. Kane says Intrepid Response offers three core services: geo-mapping, emergency notification, and a communication platform for sharing messages and photos.

When asked whether he was concerned about the incident in Brooklyn Center, Kane said he “doesn’t know the operation,” adding “I’m not going to voice concern or not concern. I know what our tool does, and it’s not intelligence operations.” Kane says the company is “completely behind the mission of law enforcement” and isn’t privy to the other tools that might leverage data from Intrepid Response. Intrepid Response does not have any data sharing policies, he says, nor does it advise agencies on data sharing, because “there’s just no need for us to do that”; he calls it a “sort of generic platform.”

Kane wouldn’t disclose how many customers Intrepid Response has, but he says the software supports law enforcement agencies, fire and other public emergency services, and some commercial vendors, and that it is “practically in all 50 states.” He says he is “not really aware of another product” that competes with Intrepid Response.

Intrepid Response lets officers collect data that can be analyzed in myriad ways, and our investigation has found that officers were compiling watch lists of people attending protests. The Minnesota Fusion Center has access to facial recognition technology through the Homeland Security Information Network, a secure network that was used during Operation Safety Net. The Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office (another OSN member agency) also uses what it refers to as investigative imaging technology, another term for facial recognition.

“This kind of informal multi-agency coordination encourages “policy shopping,” where the agency with the least restrictive privacy rules can perform surveillance that other agencies wouldn’t be able to,” says Jake Wiener, a fellow at the Electronic Privacy Information Center and an expert on fusion centers and protest surveillance. “That means overall more surveillance, less oversight, and more risk of harassment or political arrests.” Further, Intrepid could provide “a forum where many agencies can contribute, but no agency is responsible for oversight and auditing,” making it “ripe for abuse.”

It’s unclear where Duggan’s and the other journalists’ personal data went after the Minnesota State Patrol shared it via Intrepid Response. Gordon Shank, a Minnesota State Patrol public information officer, says the photos were accessible to the Minnesota Fusion Center and the Department of Natural Resources through Intrepid Response. The Minnesota State Patrol ultimately stored the photos as a PDF in an electronic folder owned by the agency. Shank also says no analytics were run on the photos, and they have not yet been deleted because of pending litigation.

An “extremely disturbing” incident

The night of April 16, police photographed Duggan’s face, full body, and media credentials. The information accompanying the images includes the coordinates of the location where the photos were taken, a time stamp, and a map of the immediate area. Sokotoff’s file, also dated April 16, 2021, contains the same data in the same format in addition to images of his state identification card.

Duggan and other eyewitnesses say that several dozen journalists were included in the cataloging activity. We have independently confirmed that six journalists were photographed in the same manner as Duggan, and they all called the incident concerning. Many said they asked officers why their data was being collected and where it was being stored, but the officers declined to reply.

“We committed no crime, and yet records were kept on us. I believe this is a step in the direction of authoritarianism, and has a chilling effect on the free press,” says Chris Taylor, a freelancer working on behalf of the Minneapolis Television Network who was photographed by Minnesota State Patrol. “It’s against the ethos of being American.”

Sokotoff, a student photojournalist at the University of Michigan, also live-tweeted the incident. “It was unlike anything I’d seen and was extremely disturbing,” he says.

All the incidents appeared to have been initiated by the Minnesota State Patrol, which recently settled a lawsuit regarding its treatment of journalists during the protests. On April 17, over 25 media companies, including local outlets Minnesota Public Radio and the Star Tribune as well as the New York Times, Gannett, the Associated Press, and Fox/UTC Holdings, signed a letter sent a letter to Minnesota Governor Tim Walz; a temporary restraining order was issued to the Minnesota State Patrol that same day. The state patrol publicly responded through a press release issued by Operation Safety Net, which stated that officers “photographed journalists and their credentials and driver’s licenses at the scene in order to expedite the identification process… This process was implemented in response to media concerns expressed last year about the time it took to identify and release journalists.”

The tactic “doesn’t appear to serve any law enforcement purpose beyond intimidating reporters who are doing their job,” said Parker Higgins, director of advocacy for the Freedom of the Press Foundation, which has been investigating the incident. “And now, almost a full year later, there still aren’t clear answers as to why the photos were taken, how the images were shared or stored, and whether that data remains in law enforcement databases.”