As the covid pandemic raged in late 2020, all eyes turned briefly from our troubled planet to our planetary neighbor Venus. Astronomers had made a startling detection in its cloud tops: a gas called phosphine that on Earth is created through biological processes. Speculation ran wild as scientists struggled to understand what they were seeing.

Now, a mission due to be launched next year could finally begin to answer the question that has excited astronomers ever since: Could microbial life be belching out the gas?

Although later studies questioned the detection of phosphine, the initial study reignited interest in Venus. In its wake, NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) selected three new missions to travel to the planet and investigate, among other questions, whether its conditions could have supported life in the past. China and India, too, have plans to send missions to Venus. “Phosphine reminded everybody how poorly characterized [this planet] was,” says Colin Wilson at the University of Oxford, one of the deputy lead scientists on Europe’s Venus mission, EnVision.

But the bulk of those missions would not return results until later in the 2020s or into the 2030s. Astronomers wanted answers now. As luck would have it, so did Peter Beck, the CEO of the New Zealand–based launch company Rocket Lab. Long fascinated by Venus, Beck was contacted by a group of MIT scientists about a bold mission that could use one of the company’s rockets to hunt for life on Venus much sooner—with a launch in 2023. (A backup launch window is available in January 2025.)

Phosphine or no, scientists think that if life does exist on Venus, it might be in the form of microbes inside tiny droplets of sulfuric acid that float high above the planet. While the surface appears largely inhospitable, with temperatures hot enough to melt lead and pressures similar to those at the bottom of Earth’s oceans, conditions about 45 to 60 kilometers above the ground in the clouds of Venus are significantly more temperate.

“I’ve always felt that Venus has got a hard rap,” says Beck. “The discovery of phosphine was the catalyst. We need to go to Venus to look for life.”

Details of the mission, the first privately funded venture to another planet, have now been published. Rocket Lab has developed a small multipurpose spacecraft called Photon, the size of a dining table, that can be sent to multiple locations in the solar system. A mission to the moon for NASA was launched in June. For this Venus mission, another Photon spacecraft will be used to throw a small probe into the planet’s atmosphere.

That probe is currently being developed by a team of fewer than 30 people, led by Sara Seager at MIT. Launching as soon as May 2023, it should take five months to reach Venus, arriving in October 2023. At less than $10 million, the mission—funded by Rocket Lab, MIT, and undisclosed philanthropists—is high risk but low cost, just 2% of the price for each of NASA’s Venus missions.

“This is the simplest, cheapest, and best thing you could do to try and make a great discovery,” says Seager.

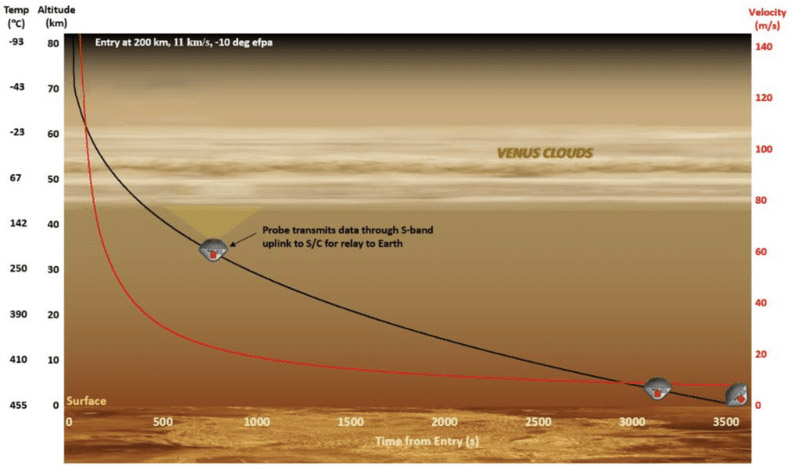

The probe is small, weighing just 45 pounds and measuring 15 inches across, slightly larger than a basketball hoop. Its cone-shaped design sports a heat shield at the front, which will bear the brunt of the intense heat generated as the probe—released by the Photon craft before arrival—hits the Venusian atmosphere at 40,000 kilometers per hour.

Inside the probe will be a single instrument weighing only two pounds. There is no camera on board to take images as the probe falls through the clouds of Venus—there simply isn’t the radio power or time for it to beam much back to Earth. “We have to be very, very frugal with the data that we’re sending back,” says Beck.

It is not images scientists are after, however, but a close-up inspection of Venus’s clouds. That will be provided by an autofluorescing nephelometer, a device that will flash an ultraviolet laser on droplets in Venus’s atmosphere to determine the composition of molecules inside them. As the probe descends, the laser will shine outwards through a small window. It will excite complex molecules—potentially including organic compounds—in the droplets, causing them to fluoresce.

“We’re going to look for organic particles inside the cloud droplets,” Seager says. Such a discovery wouldn’t be proof of life—organic molecules can be created in ways that have nothing to do with biological processes. But if they were found, it would be a step “toward us considering Venus as a potentially habitable environment,” says Seager.

Only direct measurements in the atmosphere can look for the types of life we think could still exist on Venus. Orbiting spacecraft can tell us a great deal about the planet’s broad characteristics, but to really understand it we must send probes to study it up close. The attempt by Rocket Lab and MIT is the first with such a clear focus on life, although the Soviet Union and the US sent probes to Venus in the 20th century.

The mission will not look for phosphine itself because an instrument capable of doing so would not fit in the probe, Seager says. But that could be a job for NASA’s DAVINCI+ mission, set to launch in 2029.

The Rocket Lab–MIT mission will be short. As the probe falls, it will have just five minutes in the clouds of Venus to perform its experiment, radioing its data back to Earth as it plummets towards the surface. Additional data could be taken below the clouds, if the probe survives. An hour after entering the atmosphere of Venus, the probe will hit the ground. Communications will probably be lost some time before that.

Jane Greaves, who led the initial study of phosphine on Venus, says she is looking forward to the mission. “I’m very excited about it,” she says, adding that it has a “great chance” at detecting organic materials, which “might mean life is there.”

Seager hopes this is just the start. Her team is planning future missions to Venus that will be able to follow up on results from this tentative glimpse into the atmosphere. One idea is to place balloons in the clouds, like the Soviet Vega balloons in the 1980s, which could carry out longer investigations.

“We need more time in the clouds,” says Seager—ideally with something larger that has more instruments on board. “An hour would be enough to search for complex molecules, not just see their imprint.”

This first mission could showcase the role that private enterprise can play in planetary science. While agencies like NASA continue to send multibillion-dollar machines out into the orbit, Rocket Lab and others can fill a niche for smaller vehicles, perhaps in rapid response to discoveries like phosphine on Venus.

Could this small but mighty effort be the first to find evidence of alien life in the universe? “The chances are low,” says Beck. “But it’s worth a try.”