The draining 996 work schedule—named for the expectation that employees work 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week—has persisted in Chinese companies for years despite ongoing public outcry. Even Alibaba co-founder Jack Ma once called it a “huge blessing.”

In early October this year, it seemed the tide might have been turning. After hopeful signs of increased government scrutiny in August, four aspiring tech workers initiated a social media project designed to expose the problem with the nation’s working culture. A publicly editable database of company practices, it soon went viral, revealing working conditions at many companies in the tech sector and helping bring 996 to the center of the public’s attention. It managed to garner 1 million views within its first week.

But the project—first dubbed Worker Lives Matter and then Working Time—was gone almost as quickly as it appeared. The database and the GitHub repository page have been deleted, and online discussions about the work have been censored by Chinese social networking platforms.

The short life of Working Time highlights how difficult it is to make progress against overtime practices that, while technically illegal in China, are still thriving. But some suspect it won’t be the last anonymous project to take on 996. “I believe there will be more and more attempts and initiatives like this,” says programmer Suji Yan, who has worked on another anti-996 project. With better approaches to avoiding censorship, he says, they could bring even more attention to the problem.

Tracking hours

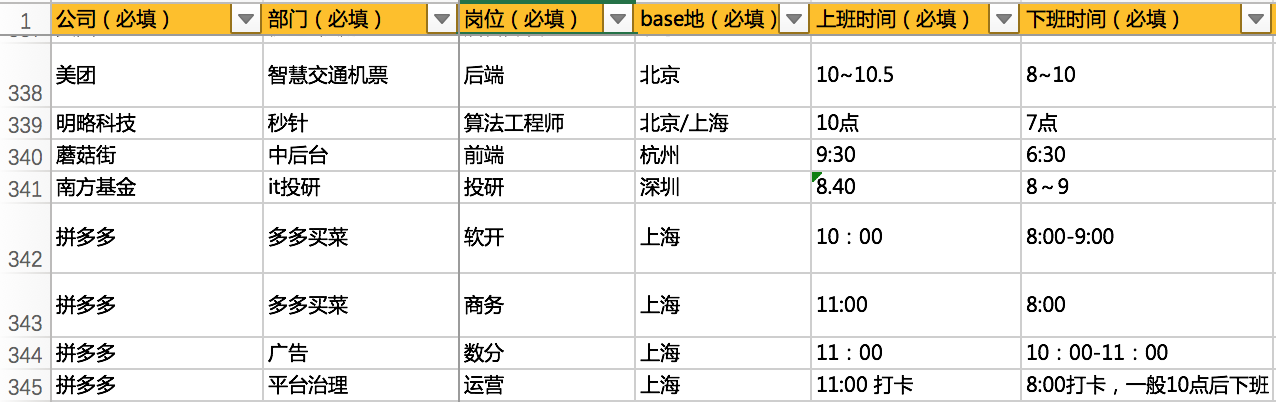

Working Time started with a spreadsheet shared on Tencent Docs, China’s version of Google Docs. Shortly after it was posted, it was populated with entries attributed to companies such as Alibaba, the Chinese-language internet search provider Baidu, and e-commerce company JD.com.

“9 a.m., 10:30 p.m.–11:00 p.m., six days a week, managers usually go home after midnight,” read one entry linked with tech giant Huawei.

“10 a.m., 9 p.m. (off-work time 9 p.m., but our group stays until 9:30 p.m. or 10 p.m. because of involution,” noted another entry (“involution” is Chinese internet slang for irrational competition).

Within three days, more than 1,000 entries had been added. A few days later, it became the top trending topic on China’s Quora-like online forum Zhihu.

As the spreadsheet grew and got more public attention, one organizer, with the user name 秃头才能变强 (“Only Being Bald Can Make You Strong”), came out on Zhihu to share the story behind the burgeoning project.

“Four of us are fresh college and master’s degree graduates who were born between 1996 and 2001,” the organizer said. Initially, the spreadsheet was just for information sharing, to help job hunters like themselves, they said. But as it got popular, the organizers decided to push from information gathering to activism. “It is not simply about sharing anymore, as we bear some social responsibility,” 秃头才能变强 wrote.

The spreadsheet filled a gap in China, where there is a lack of company rating sites such as Glassdoor and limited ways for people to learn about benefits, office culture, and salary information. Some job seekers depend on word of mouth, while others reach out to workers randomly on the professional networking app Maimai or piece together information from job listings.

“I have heard about 996, but I was not aware it is that common. Now I see the tables made by others, I feel quite shocked,” Lane Sun, a university student from Nanjing, said when the project was still public.

Against 996

According to China’s labor laws, a typical work schedule is eight hours a day, with a maximum of 44 hours a week. Extra hours beyond that require overtime pay, and monthly overtime totals are capped at 36 hours.

But for a long time, China’s tech companies and startups have skirted overtime caps and become notorious for endorsing, glamorizing, and in some cases mandating long hours in the name of hard work and competitive advantage.

In a joint survey by China’s online job site Boss Zhipin and the microblogging platform Weibo in 2019, only 10.6% of workers surveyed said they rarely worked overtime, while 24.7% worked overtime every day.

Long work hours can benefit workers, Jack Ma explained in 2019. “Since you are here, instead of making yourself miserable, you should do 996,” Ma said in a speech at an internal Alibaba meeting that was later shared online. “Your 10-year working experience will be the same as others’ 20 years.”

But the tech community had already started to fight back. Earlier that year, a user created the domain 996.icu. A repository of the same name was launched on GitHub a few days later. The name means that “by following the 996 work schedule, you are risking yourself getting into the ICU (intensive care unit),” explains the GitHub page, which includes regulations on working hours under China’s labor law and a list of more than 200 companies that practice 996.

Within three days, the repository got over 100,000 stars, or bookmarks, becoming the top trending project on GitHub at that time. It was blocked not long after by Chinese browsers including QQ and 360, ultimately disappearing entirely from the Chinese internet (it is still available through VPNs).

The 996.icu project was quickly followed by the Anti-996 License. Devised by Yan and Katt Gu, who has a legal background, the software license allows developers to restrict the use of their code to those entities that comply with labor laws. In total, the Anti-996 License has been adopted by more than 2,000 projects, Yan says.

State involvement

Today, 996 is facing increasing public scrutiny from both Chinese authorities and the general public. After a former employee at the agriculture-focused tech firm Pinduoduo died in December 2020, allegedly because of overwork, China’s state-run press agency Xinhua called out overtime culture and advocated for shorter hours.

And on August 26, China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and the Supreme People’s Court jointly published guidelines and examples of court cases on overtime, sending reminders to companies and individuals to be aware of labor laws. But even though authorities and state media seem to be taking a tougher stand, it is unclear when or if the rules that make 996 illegal will be fully enforced.

Some companies are making changes. Anthony Cai, a current employee of Baidu, says working six days a week is quite rare in big companies nowadays. This year, several tech companies including and ByteDance, the developer of TikTok, canceled “big/small weeks,” an emerging term in China that refers to working a six-day schedule every other week. “Working on Saturday is not that popular anymore,” Cai says. “However, staying late at the office is still very common, which is not usually counted as overtime hours.”

In the future, companies may have to scale further back on overtime to attract young applicants. Faper Fu, a university student in Nanjing, says he has little interest in accepting 996 when he enters the job market. “If I am getting paid a lot, I may consider it,” he says. “But it is not my long-term plan 100%. Having work and life balance is very important to me.”

Cary Cooper, a professor of organizational psychology and health at Alliance Manchester Business School in the UK, thinks Chinese companies will pull away from overtime culture when they see evidence of the impact that long hours have on the health and productivity of workers. “There is no evidence that if people consistently work long hours, their productivity level will increase—it’s the opposite,” he says.

In the meantime, Cooper says, younger generations “won’t stop fighting for a good quality of working life.”

“996 will only make human machines,” wrote 秃头才能变强. “And the only result of a dry human battery is being thrown into the trash can after the battery goes dry.”