As a globally unprecedented 70-day heat wave continues to hold its grip on southern China, with the highest temperature as much as 113°F (45°C), severe droughts and shortages in the hydropower supply are wreaking havoc on the lives of residents. Electric vehicle owners are one group particularly feeling the heat. Since public charging posts are temporarily closed or restricted and many owners don’t have a private charging post, they’ve suddenly found themselves facing serious difficulties in powering their daily commutes.

The adoption of EVs (or new energy vehicles, as they are referred to in China) is often seen as a high point in China’s fight against climate change. But extreme weather, which increasingly disrupts power grids around the world, also serves as a reminder of the weaknesses in the charging infrastructure that keeps EVs running.

The record-breaking heat wave in China, which started back in June, has evaporated over half the hydroelectricity generation capacity in Sichuan, a southwestern province that usually gets 81% of its electricity from hydropower plants. That decreased energy supply, at a time when the need for cooling has increased demand, is putting industrial production and everyday life in the region on pause.

And as the power supply has become unreliable, the government has instituted EV charging restrictions in order to prioritize more critical daily electricity needs.

As Chinese publications have reported, finding a working charging station in Sichuan and the neighboring region Chongqing—a task that took a few minutes before the heat wave—took as long as two hours this week. The majority of public charging stations, including those operated by leading EV brands like Tesla and China’s NIO and XPeng, are closed in the region because of government restrictions on commercial electricity usage.

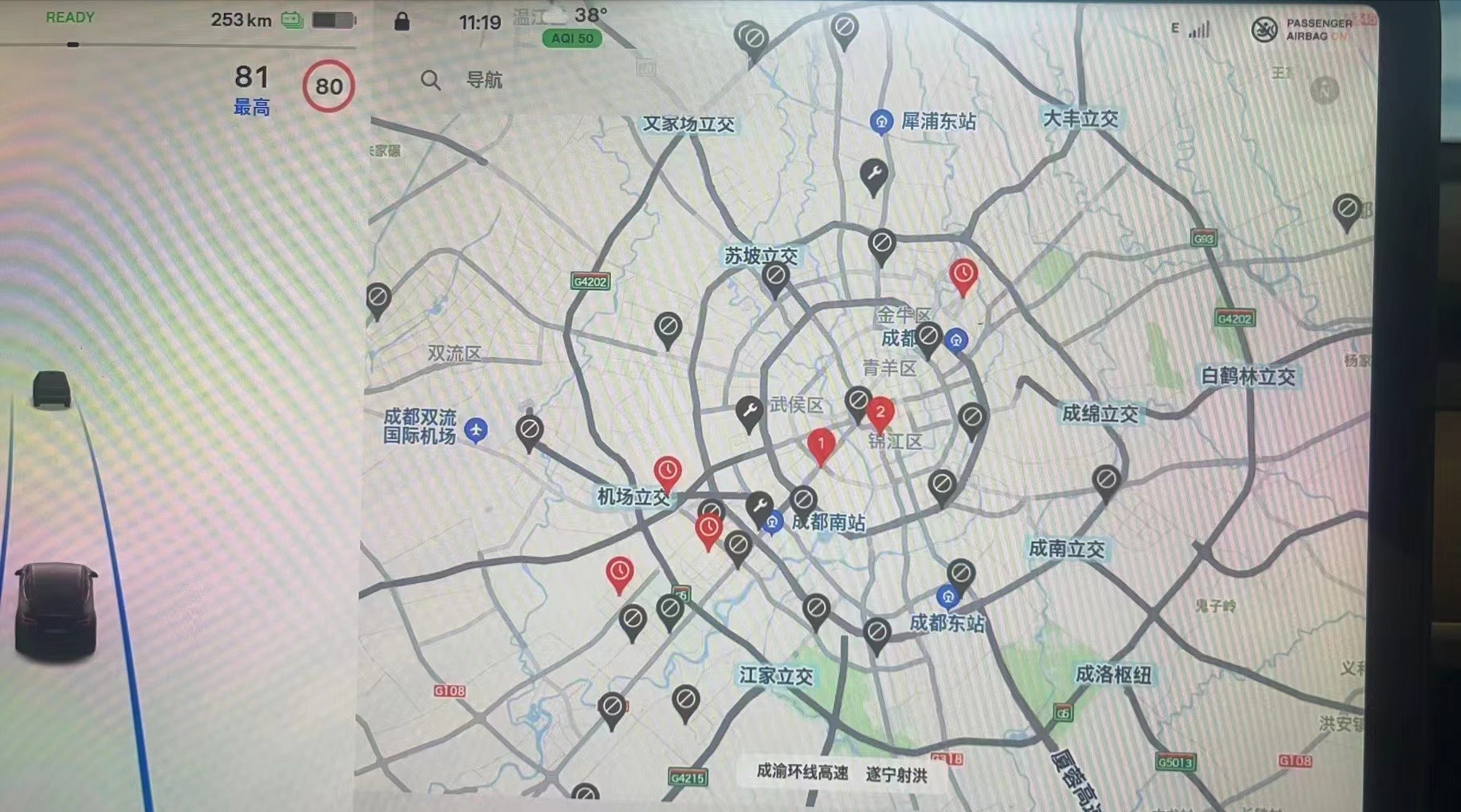

A screenshot sent to MIT Technology Review by a Chinese Tesla owner in Sichuan, who asked not to be named for privacy reasons, shows that on August 24, only two of the 31 Tesla Supercharger Stations in or near the province’s capital city of Chengdu were working as normal.

In addition to facing mandatory service suspensions, EV owners are also being encouraged or forced to charge only during off-peak hours. In fact, the leading domestic operator, TELD, has closed over 120 charging stations in the region from 8 a.m. to midnight, the peak hours for electricity usage. State Grid, China’s largest state-owned electric utility company, also builds and operates EV charging stations; it announced on August 19 that in three provinces that have over 140 million residents and 800,000 electric vehicles in total, the company will offer 50% off coupons if drivers charge at night. State Grid is also reducing the efficiency of 350,000 charging posts during the day, so the individual charging time for vehicles would be five to six minutes longer but the total power consumed during peak hours would go down.

The impact is evident in videos shared on Chinese social media, which show long lines of EVs waiting outside the few working charging stations, even after midnight. Electric taxi drivers have been hit especially hard, as their livelihoods depend on their vehicles. “I started waiting in the line at 8:30 p.m. yesterday and I only started charging at around 5 a.m.,” a Chengdu taxi driver told an EV influencer. “You are basically always waiting in lines. Like today, I didn’t even get much business, but I’m in the line again now. And the battery is going down quickly.”

The charging challenges are also pushing some people back into using fossil fuel. The Tesla owner in Sichuan is planning to visit Chengdu for work this week but decided to drive his other car, a gas-powered one, for fear that he wouldn’t find a place to recharge before returning home. Another driver from Chengdu, who owns a plug-in hybrid, told MIT Technology Review that she switched to gas this week even though she usually sticks to electricity because it’s slightly cheaper.

The sudden difficulty of charging in Sichuan and neighboring provinces has caught the EV industry by surprise. “A large-scale power shortage like this is still something we’ve never seen [in China],” says Lei Xing, an auto industry analyst and the former chief editor at China Auto Review. He says the climate disaster is reminding the industry that while China leads the world on many EV adoption metrics, there are still infrastructure weaknesses that need to be addressed. “It feels like China already has a good charging infrastructure … but once something like these power restrictions happens, the problems are exposed. All EV owners who rely on public charging posts are having troubles now,” Xing says.

Thanks to government subsidies, strong domestic brand competition, and prices as low as $4,000 per car, China has been one of the world leaders in EV adoption. The total number of EVs in China surpassed 10 million in July—the largest in the world and four times the figure in the US. In 2021 alone, there were more EVs sold in China than in all other countries combined.

But as EV ownership grows, the development of charging infrastructure is lagging behind—and this summer’s heat wave has become an urgent reminder of why that’s a problem.

One significant obstacle is the lack of private charging posts. “A far larger percentage of Chinese [than Americans] live in apartment complexes,” says Daniel Kammen, a professor of energy at the University of California, Berkeley, who has studied the modernization of the electric grid in China. “And the EVs are concentrated massively in China. They’re in the cities, not in the rural areas.” For apartment-dwelling EV owners, even a fixed parking spot is difficult and costly to obtain, let alone a private charging post.

In situations like the heat wave, private charging posts, which are considered part of one’s residential power consumption, would have provided a stable alternative to the suspended public charging stations. Restrictions on residential power use, which were also ordered in parts of Sichuan this year, happen much less often and are seen as the last resort in addressing power shortages.

Chinese living patterns also mean it’s harder to establish distributed power generation and storage through options like residential solar panels, which would complement central power sources when there are shortages. “For example, in my house, where we have two electric vehicles, and rooftop solar, and a backup storage battery in our garage, it makes much more sense to charge our electric vehicles during the day because we have direct solar,” says Kammen. But this is not the norm in China, where there are solar panels on only 2.8% of rooftops—overwhelmingly concentrated in rural areas.

Looking ahead, there’s hope that the current power shortage in southern China will improve soon: the country’s National Meteorological Center predicts that the heat wave will wind down when rain comes to the region beginning August 29. But even if it eases, building a resilient electric grid and diversifying EV charging methods will be crucial to fully support a booming domestic EV industry that experts think is unlikely to shrink even after this challenging period. “I personally think there will be a short-term impact that won’t change the expected total sales of new energy vehicles this year or after,” says Tian Yongqiu, an independent auto industry analyst based in China.

In the long term, according to Kammen, the solution in China will likely involve a more distributed system of energy storage and better long-distance power transmission, as well as alternative clean energy sources, like large-scale offshore wind or solar farms. EVs themselves can be part of the answer, too. Some EV companies have been experimenting with two-way charging, so that instead of being a burden to the grid, EV batteries have the potential to feed power back to the grid when needed. Mass application of this technology, though, remains a distant hope.

At the very least, what happened this summer will provide a series of crucial and urgent lessons. Xing estimates that by 2025, more than half the new cars sold in China could be EVs. “If there are 30 million cars sold in total, 15 million of them will be new energy vehicles. How can the electric grid satisfy that kind of demand? That’s the long-term question,” he says. “[What happened] this time was a reminder—a wake-up call.”