About 35 million Americans suffer from digestive issues such as constipation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and gastroparesis (partial stomach paralysis). These so-called motility disorders, in which food fails to move through the system properly, are often diagnosed using endoscopy, nuclear imaging studies, or x-rays.

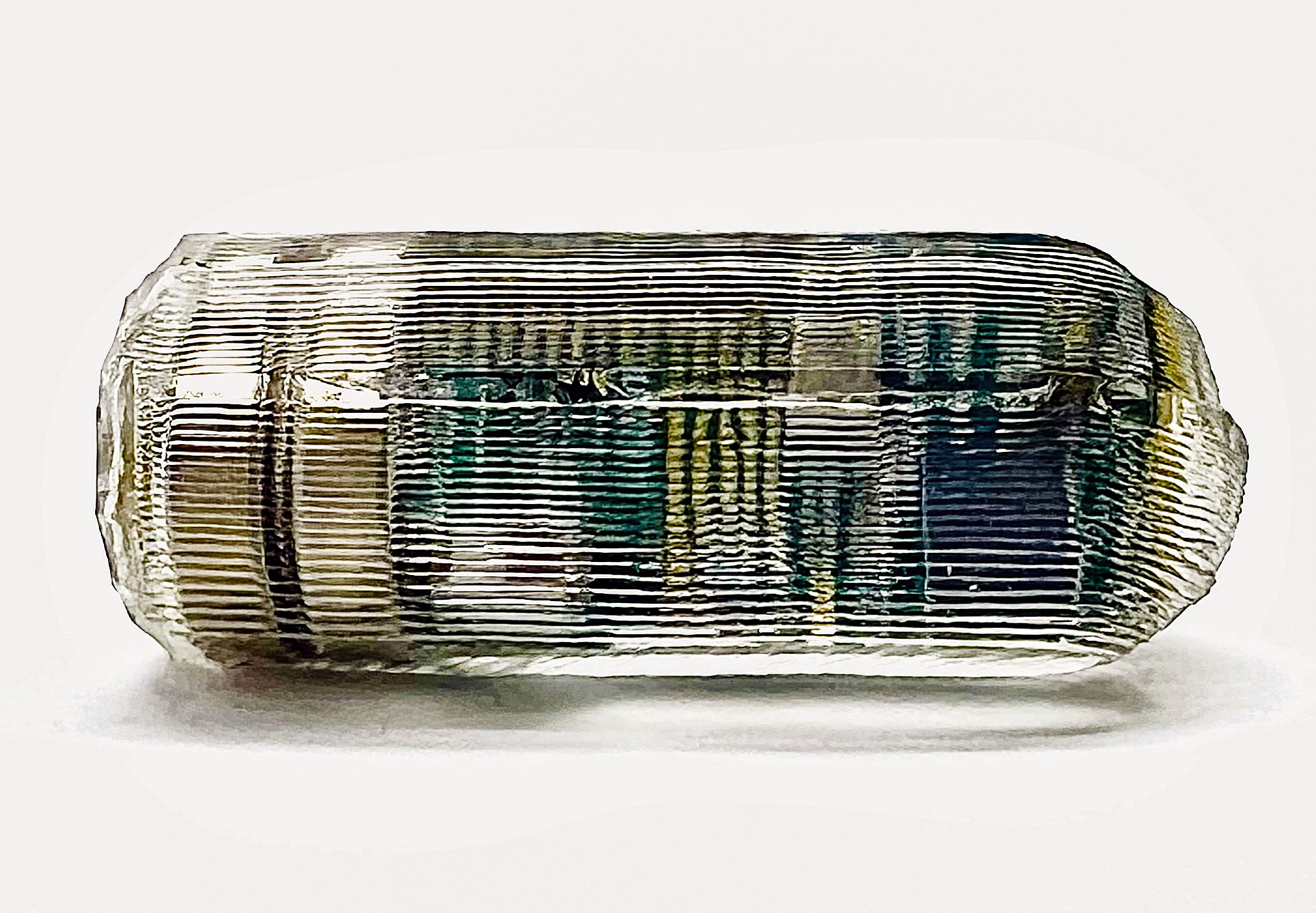

But engineers at MIT and Caltech have come up with a less invasive alternative: an ingestible sensor whose location can be monitored on its trip through the body. The innovation could someday make it much easier to pinpoint the source of the trouble without a hospital visit. In a new study, the researchers showed that they could use their system to track the sensor as it moved through the digestive tract of large animals.

The tiny sensor measures a magnetic field produced by an electromagnetic coil outside the body. Its progress can be calculated from the measurements because the field’s strength weakens with distance from the coil. The hope is that doctors could use this information to determine what part of the digestive tract is causing a slowdown and help decide on a treatment.

To help pinpoint the swallowed pill’s location, a second sensor remains outside the body as a reference point. This sensor could be taped to the skin, while the coil could be placed in a pocket or backpack, or even on the back of a toilet. A wireless transmitter sends the magnetic field measurement to a nearby computer or smartphone.

“The ability to characterize motility without the need for radiation, in-hospital visits, or more invasive placement of devices could lower the barrier for people to be evaluated,” says Giovanni Traverso, a senior author of the study, who is an associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT and a gastroenterologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The researchers now hope to work with collaborators on manufacturing processes and eventually to test the system in humans.