Until Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Nord Stream 1 and 2 gas pipelines were a key part of Europe’s energy infrastructure. In the fourth quarter of 2021, the Nord Stream lines supplied 18% of all Europe’s gas imports. Half of Russia’s gas imports to Europe came through Nord Stream 1—a record high. (Nord Stream 2, which has been completed, has not yet come online after Germany withheld its certification following the invasion.)

Since then, Nord Stream has become a geopolitical pawn as Russia has retaliated for economic sanctions imposed upon it after the invasion. In July, Russia took the pipeline offline for scheduled maintenance but never returned it to full capacity; by August, Russia’s state energy company had declared an unplanned outage.

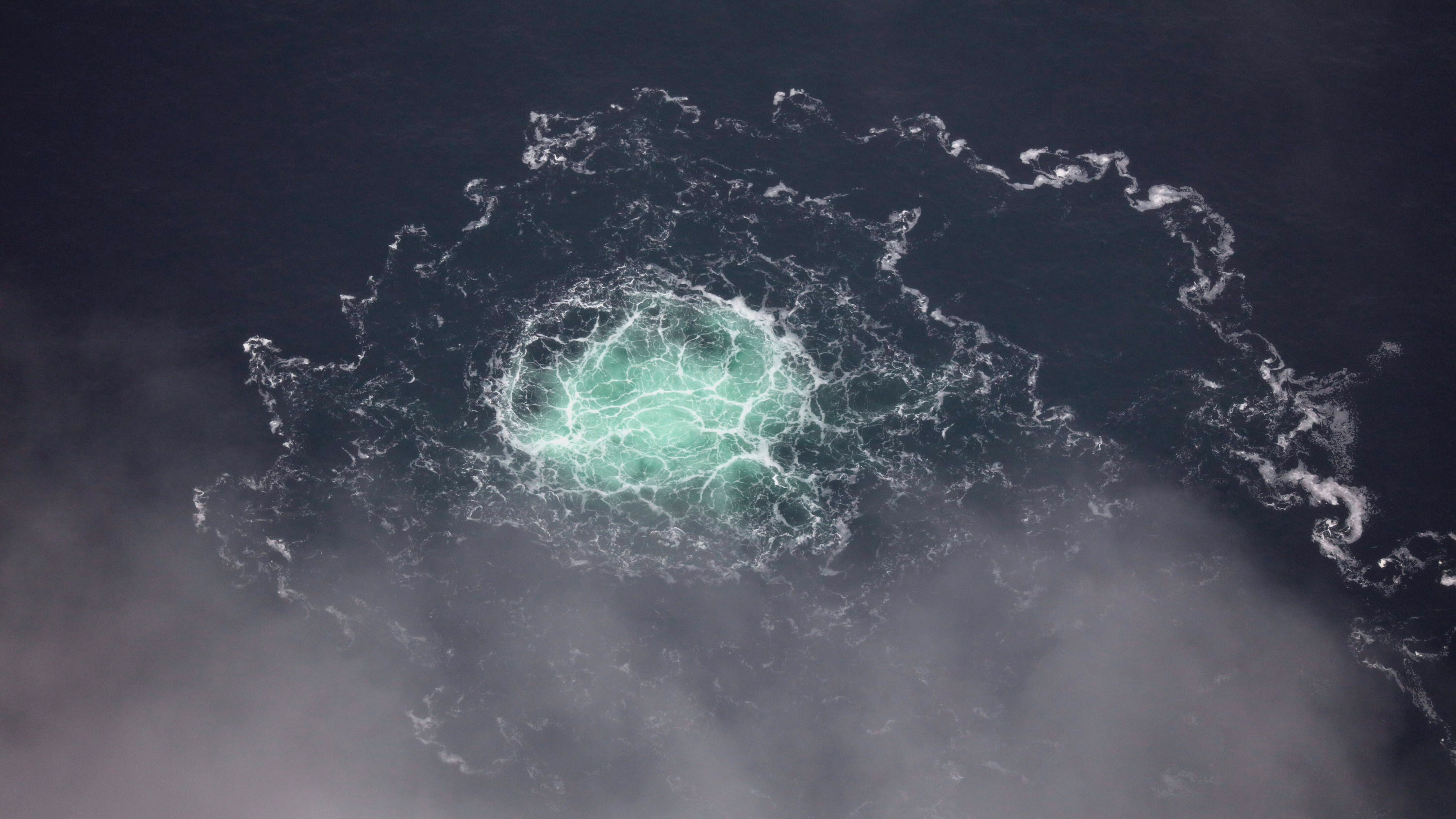

Then, in late September, unexpected damage caused four leaks in the subsea pipeline system. Everyone except Russia believes it’s sabotage by the pariah state as it attempts to squeeze supplies ahead of a tricky winter energy shortage in Europe, where countries are already planning to cut back on energy use.

Now the race is on to fix the vital pipelines before winter—if that’s even possible. The Swiss-based joint venture behind Nord Stream, which is 51% owned by the Russian state energy firm Gazprom, is uncertain whether the issues will ever be fixed. The head of Russia’s parliamentary energy committee, Pavel Zavalny, thinks the trouble could be resolved in six months—conveniently after the winter, when the supplies are needed most.

What we do know is that any mission will be an unprecedented challenge for the oil and gas sector, requiring complex robotics and imaginative engineering.

And while we don’t even know for sure how bad the situation is, the damage is expected to be significant: the September 26 blasts believed to have caused the pipeline ruptures registered 2.2 on the Richter scale, according to the Swedish National Seismic Network. Swedish and Danish investigators, who have taken the lead on probing the leaks because they happened nearest to their countries, have said that they were caused by blasts equivalent to “several hundred kilos of explosives.”

“These are massive explosions that may have damaged this pipeline over a greater distance [than we know of],” says Jilles van den Beukel, an independent energy analyst who worked for Shell for 25 years, most recently as a principal geoscientist. “Perhaps this pipeline is not in its original position anymore.”

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen has called the incident a “deliberate disruption of active European energy infrastructure.” US president Joe Biden called it a “deliberate act of sabotage.” But while the culprit may seem obvious, a Kremlin spokesperson says pointing the finger of blame at the Russians is “predictably stupid.”

No matter who did it, it was deliberate, says van der Beukel. “These pipelines normally simply don’t break down,” he says. The steel Nord Stream pipes are 1.6 inches thick, with up to another 4.3 inches of concrete wrapped around them. Each of the 100,000 or so sections of the pipeline weighs 24 metric tons.

“These kinds of leaks are described as a one-in-100,000-years kind of thing,” he says. “The only way these kinds of things happen is sabotage.”

Because the pipeline was not in active service given the geopolitical situation, the environmental impact—while still concerning—is not as great a problem as it could have been. According to estimates, the volume of gas likely to have leaked from the pipeline could have resulted in anywhere between 7.5 million and 14 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent, German and Danish authorities have told reporters. A Gazprom spokesperson told a September 30 UN Security Council meeting that the organization believed the pipelines contained around 800 million cubic meters of gas at the time of rupture, putting a potential cap on the volume of gas that could have escaped. But it’s not safe to investigate and identify potential repairs while gas is still leaking out.

Once investigators can safely get hands on, the tricky work of triaging the problems and finding solutions begins. “You assess: ‘Okay, what is the state of the pipe? What are the damages?’” says Jean-François Ribet of the Monaco-based oil and gas pipeline repair company 3X Engineering, which has previously repaired pipelines in Yemen that have been sabotaged by the likes of Al-Qaeda. That assessment can be done using an inspection robot, a remotely operated vehicle, or specialized divers.

Sending divers to the site is challenging because of the depth of the pipeline: while the known leaks are concentrated in relatively shallow waters—around 50 meters deep—the majority of the pipeline lies 80 to 100 meters underwater. And all of it will need to be inspected for potential damage.

“We’ve done repairs at that depth, but you have to use saturation diving,” says Olivier Marin, R&D and technical manager at 3X Engineering. (In saturation diving, which is used for deep-sea conditions, divers remain at the extreme depth in a specialized habitat and undergo a single decompression once the operation is over.) “You can maybe do 10 hours, but you will have to stay for one month in a hyperbaric chamber,” he says.

The repairs themselves would not be easy. There are a number of options, says Ribet. The first is to replace the damaged sections of the pipe in their totality—though that’s the costliest. “You need the same diameter, the same kind of steel grade, and so on,” he says. And you need to bring shipborne cranes that are strong enough to lift the heavy pipe segments out of the water.

The second repair option would be to install a clamp that covers the damaged sections of the pipe, essentially patching the ruptured areas. However, with an internal diameter of 1.153 meters, the Nord Stream pipelines would require huge clamps, as well as the temporary installation of an underwater caisson, a watertight chamber that would encase the section of pipeline so that engineers could work within it.

Marin believes this would be “the easiest solution.” However, he adds, it would take months to procure a clamp big enough to encase the pipeline. This method also won’t work if there turns out to be extensive damage, because it’s not feasible to build clamps big enough to cover significant holes. A third option is a composite repair that mixes the two methods: replace the worst-damaged elements of the pipeline, and clamp those that are less affected.

Ribet suggests one potentially less likely fourth option: building and installing a new pipeline section that could bypass the damaged sections, which would be left in place. Russian analysts also note that one of Nord Stream’s four individual pipelines appears not to have been affected, meaning it could continue to deliver gas, albeit at a lower rate.

There’s a further issue complicating any would-be repair work: whether it is legal. The joint venture that runs the Nord Stream 1 pipeline, Nord Stream AG, claims to be a separate entity from the company operating the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, Nord Stream 2 AG. The latter is subject to international sanctions imposed after the invasion of Russia. The sanctions are likely to slow the pipeline’s repair, believes Russian minister Zavalny, who says they may make it tricky to find vessels willing to take on the work of transporting equipment.

A spokesperson for Nord Stream AG did not reply to three requests for comment asking about how the company planned to handle the sanctions issue.

Even if repairs can be made, it’s not likely that Nord Stream will recommence supplies any time soon. One major factor that also has to be considered? As gas escapes, water rushes in. That causes corrosion. “Of course, salt water inside the pipeline is not good,” says van den Beukel. Now that gas has stopped escaping the pipeline, according to the Danish Energy Agency, the race is on to try to plug the holes using “pigs”—pipeline inspection gauges, which are used to push unwanted materials out of pipelines, usually to clean them as part of regular maintenance. The faster the pigs can be sent through the affected areas, the better to limit the long-term damage.

Whatever the eventual solution, it’s going to be difficult—and expensive—to fix.

Asked if he can think if we’ve ever seen a subsea problem on this scale before, van den Beukel has a simple answer: “No. When you talk sabotage, it’s usually onshore and on a much smaller scale,” he says. “I can’t think of anything similar to this—ever.”