In America, at least 17 people a day die waiting for an organ transplant. But instead of waiting for a donor to die, what if we could someday grow our own organs?

Last week, six years after NASA announced its Vascular Tissue Challenge, a competition designed to accelerate research that could someday lead to artificial organs, the agency named two winning teams. The challenge required teams to create thick, vascularized human organ tissue that could survive for 30 days.

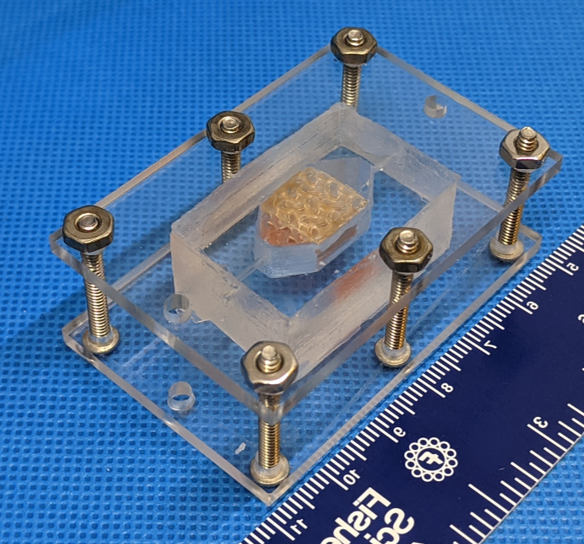

The two teams, named Winston and WFIRM, both from the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, used different 3D-printing techniques to create lab-grown liver tissue that would satisfy all of NASA’s requirements and maintain their function.

“We did take two different approaches because when you look at tissues and vascularity, you look at the body doing two main things,” says Anthony Atala, team leader for WFIRM and director of the institute.

The two approaches differ in the way vascularization—how blood vessels form inside the body—is achieved. One used tubular structures and the other spongy tissue structures to help deliver cell nutrients and remove waste. According to Atala, the challenge represented a hallmark for bioengineering because the liver, the largest internal organ in the body, is one of the most complex tissues to replicate due to the high number of functions it performs.

“When the competition came out six years ago, we knew we had been trying to solve this problem on our own,” says Atala.

Along with advancing the field of regenerative medicine and making it easier to create artificial organs for humans who need transplants, the project could someday help astronauts on future deep-space missions.

The concept of tissue engineering has been around for more than 20 years, says Laura Niklason, a professor of anesthesia and biomedical engineering at Yale, but the growing interest in space-based experimentation is starting to transform the field. “Especially as the world is now looking at private and commercial space travel, the biological impacts of low gravity are going to become more and more important, and this is a great tool for helping to understand that.”

But the winning teams must still overcome one of the biggest hurdles in tissue engineering: “Getting things to survive and maintain their function over an extended period is really challenging,” says Andrea O’Connor, head of biomedical engineering at the University of Melbourne, who calls this project, and others like it ambitious.

Equipped with a $300,000 cash prize, the first-place team—Winston—will soon have a chance to send its research to the International Space Station, where similar organ research has already taken place.

In 2019, astronaut Christina Koch activated the BioFabrication Facility (BFF), which was created by the Greenville, Indiana-based aerospace research company Techshot to print organic tissues in microgravity.

That research project has goals similar to those of NASA’s Vascular Tissue Challenge, says Eugene Boland, Techshot’s chief scientist. Except instead of 3D-printing liver tissue, their aim is to create transplantable cardiac tissue sometime in the next 10 years.

What’s different about printing organs and tissues on Earth versus doing it in space? Boland described the difference in techniques by likening the mechanics of printing with Play-Doh to printing with honey.

This year, the BFF is due for an upgrade—one that Rich Boling, vice president of corporate advancement for Techshot, says may make the potentially life-saving technology better suited for future commercialization both in space and back on Earth. In the next few months, that upgrade will involve adding the capability to print with blunt needles—the same kind used to print back on the ground.

“This has always been, for the most part, of the Earth, for the Earth. We’ve always felt like we’re doing this for things like the, for example, organ donor shortage,” Boling said.

Techshot also envisions someday using artificial tissue and organs to help treat diseases, and even congenital defects.

And artificial organs and human tissues are only two of many resources that may be in demand on future space missions. Soon, Techshot plans to enter NASA’s Deep Space Food Challenge, which will aim to develop sustainable food options for longer crewed missions. The company thinks the same 3D-printing techniques used in biomedical engineering could be just as useful in creating a food source.

Although it’ll be a long while before astronauts can implant artificial tissues into one another or chomp down on their favorite bioengineered burgers, 3D-bioprinting is starting to open up those possibilities.