When Baldwin Lee ’72 was five years old, his father told him he’d be going to MIT. The oldest male child in a Chinese immigrant family, he did as he was told, becoming valedictorian of Brooklyn Tech and enrolling at the Institute in 1968. The intense focus on science and technology felt suffocating, however, and as a sophomore he found refuge in a photography class taught by Minor White. His father sent him a Leica, and after graduating from MIT, Lee earned an MFA in photography at the Yale School of Art.

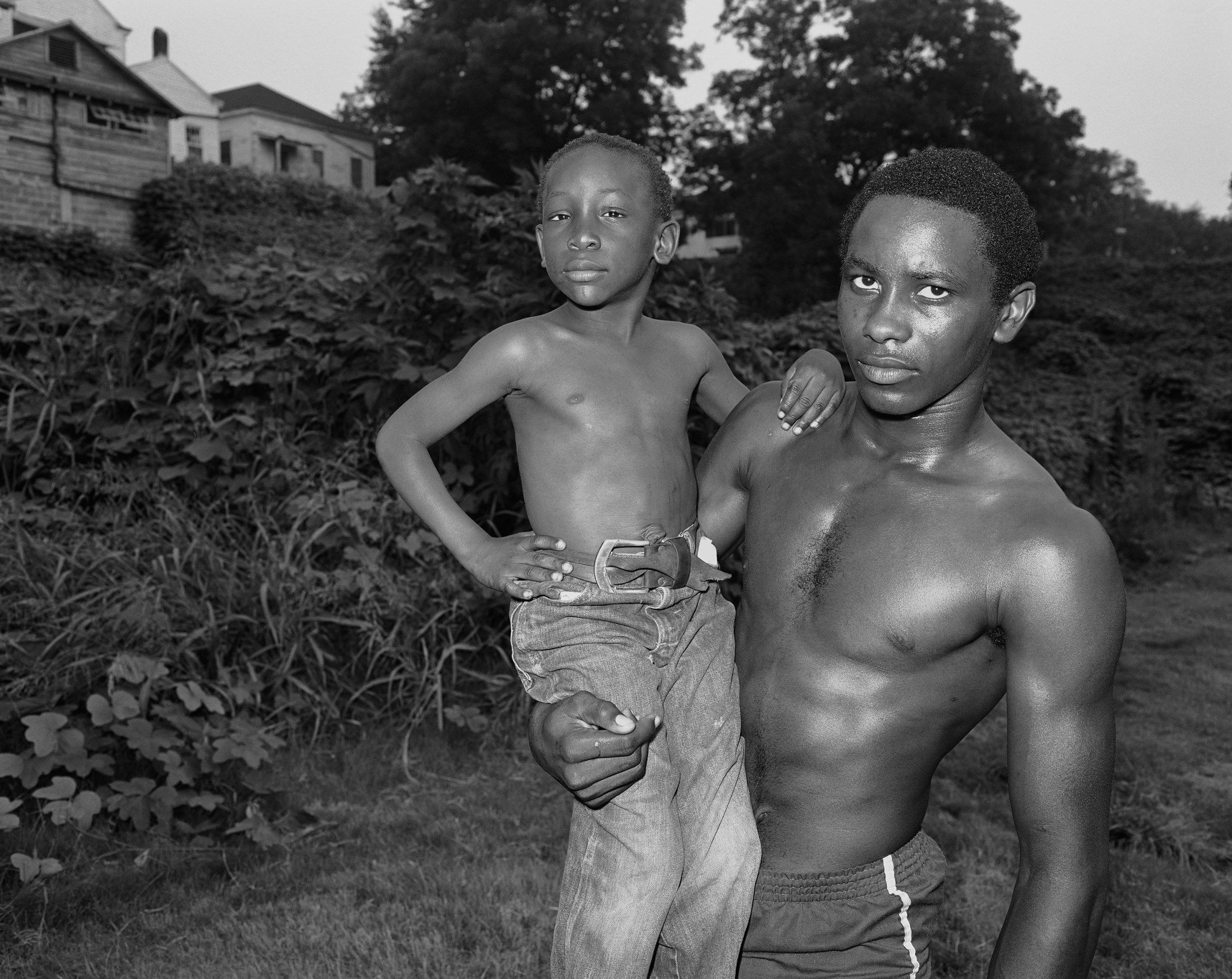

In 1983 he began a series of road trips throughout the South, capturing images of Black Americans with a tripod-mounted 4 x 5 view camera that required long exposure times and perfectly still subjects. The monograph Baldwin Lee, published this fall by Hunters Point Press, features 88 of Lee’s striking photos from this project.

A conversation with Baldwin Lee: The photographer reflects on his career

By Jessica Bell Brown

This excerpt from Jessica Bell Brown’s interview with Baldwin Lee appears in full in the monograph Baldwin Lee, edited by Barney Kulok with text by Casey Gerald, published by Hunters Point Press, 2022. Reproduced here with permission, this interview has been edited for length and clarity. The first edition of the book has sold out. The second edition will be available through Hunters Point Press in late December.

What was your upbringing like?

I am the second oldest of five children. As the first male child in a Chinese immigrant family, I was conferred a special status, with special expectations. My father told me when I was five years old that I would go to MIT, the typical immigrant aspiration. My father and mother were both from prosperous families; they grew up and married in China. Once here, my father went to the Pratt Institute in New York to study architecture. His uncle owned a noodle-manufacturing business in Chinatown but fell ill and my father unwillingly took over, never getting the chance to practice architecture. He was an accomplished artist who painted and photographed.

How was creativity fostered for you growing up?

Creativity was never brought up in my childhood. The only emphasis was success in school. In the 1950s and 1960s, Chinatown was an insular enclave. My primary school had 500 students, only two of whom were not Chinese. I had very little contact with anyone who was not Chinese, as if I had grown up in a tiny remote town. In 1968 I was valedictorian of Brooklyn Tech and was accepted to MIT. Once there, I was miserable. The environment of science and technology was suffocating. There was no option—because of my obligation to my family—to transfer to another school, and I persevered in silence. Redemption occurred by surprise in my sophomore year when I enrolled in a photography class taught by Minor White. Although I grew up in Manhattan, I knew very little about art. The first time I went to museums was on a class trip.

Can you recall your first camera? At what point did you start photographing seriously?

My first camera was a Kodak Hawkeye, which took 120 roll film. It was a prophetic acquisition in that it was given to me by my father when I was in the hospital recovering from an eye injury. I had a wonderful view of the 59th Street Bridge, which became my first subject. When I was at MIT, my father, ever supportive of my education, sent me a Leica when I told him I enrolled in a photography class. He didn’t realize that photography would become my life for the next 50 years.

Your work seems to have two formative influences: your teachers Minor White at MIT and Walker Evans at Yale University. How did your experiences with each of them differ?

I would tell my students that my photography teachers were the equivalent of having studied with Matisse and Cézanne. I am glad Minor White preceded Walker Evans, because White provided an introduction to the aesthetics of art. He was an oasis in a sea of science and technology. His life as an artist and his thoughts and actions were a lifeline that not only enabled me to survive at MIT, but were an introduction to the viability of a life endeavor I had not known. He had his students read George Gurdjieff and Carlos Castaneda. Complementing this revolutionary agenda was the political/social/cultural revolution precipitated by the war in Vietnam and racism in America. My college experience certainly was not what my father had in mind.

In 1973 I began to study under Walker Evans at the Yale School of Art in pursuit of an MFA degree in photography. Evans as a teacher was indifferent at best. There were weekly seminars with the eight graduate students where Evans would disinterestedly leaf through a stack of our photographs, occasionally noting one as interesting. The reason to be at Yale was not to have Evans teach from a prepared syllabus, but rather to have the opportunity to be in the presence of the history of photography. I was exceedingly fortunate to have been selected by Evans to serve as his personal printer during my second year at Yale. This allowed me to frequently stay at his house in Connecticut, which offered me a glimpse of an unguarded giant.

The two-hour drive from New Haven to Cambridge afforded me the opportunity to shuttle between Evans and White in order to compare and contrast the two. Neither man held the other in high esteem. Evans considered White to be flawed by pretentiousness and affect. White saw Evans as not much more than a transcriber of fact. It was difficult to hide their respective opinions.

What kind of equipment did you use?

I worked with a tripod-mounted 4 x 5 view camera. This type of camera required long exposure times that necessitated standing perfectly still. There was no possibility of making spontaneous or surreptitious photographs. The crucial aspect in making the photograph involved my issuing verbal directions, asking for extremely specific movement of the figure and glance. This is not unlike how a sculptor making a figurative piece conceives of specific gestures and repositions various parts of the body. What I was desperately trying to do was re-create what I had seen before I approached my subject. This, after all, was why I stopped. There is a beauty in this process that exploits the unintended.

Walk me through your working methods, from driving around from state to state on road trips to printing and editing: Were you traveling alone each time? How did you decide where to stop when you were on the road?

I always traveled alone. My trips were very demanding, and having to accommodate a fellow traveler would not have been possible. The process by which I made my photographs was straightforward but intuitive. It would start with the unfolding of a paper map of the Southeast, and I would arbitrarily make a decision to travel north, south, east, or west from my home in Knoxville. I thought that after about a hundred miles I was far enough from my known world to be prepared to accept the new.

Upon arrival in a town or city, my first concern was to find the area where Black Americans lived and worked. This was almost always easy to do: drive away from rich residential and business areas toward the edges of town, where indicators of success were replaced with the stigma of neglect. If I had trouble finding these places, I would visit the town police station, telling them that I was a photographer with expensive cameras, and handed over a highlighter marker, asking them to circle areas I should avoid. Of course, I did the opposite.

You can’t take pictures from your car—you have to be on foot. Walking with a big tripod-mounted camera on your shoulder allows a reciprocal process of issuing an invitation to be looked at in return for an opportunity to look. I would approach my potential subjects, explain in as detailed a manner as possible what I had seen, and ask for permission to take a photograph. Of course, small talk—where was I from, who would see the photograph, why I selected them—would sometimes ensue. Often permission was granted with no discussion at all. Looking is a two-way street. Not only is the photographer looking, but the potential subject is looking too. What the subject sees carries great weight. For some reason, people would see me positively. I am not sure if it was my race, gender, physicality, dress, demeanor, or anything else. If in a day I asked 20 people for permission to make photographs, 19 would say yes.

I must have taken, I don’t know, 30 trips, maybe more. From the spring of ’83 on my first trip, every chance I had, any break from teaching, I would be out on the road. So it would be typical in a given summer for me to make four or five trips.

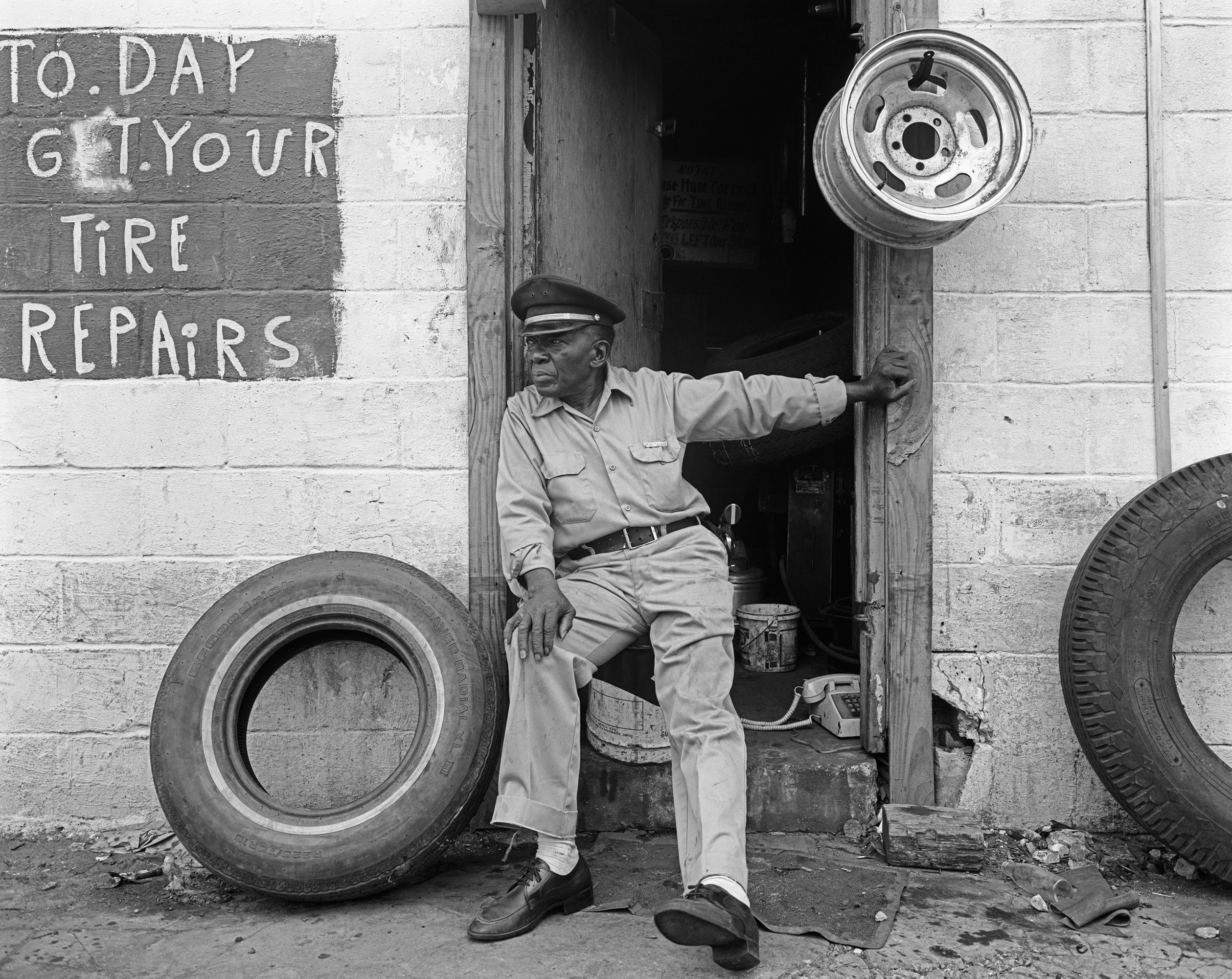

The image in Marion, Arkansas (1985) is a really interesting distillation of some of the driving themes in your work. This type of placement of the subject against a form of architecture is quite interesting. Thinking about who we are in relation to our government, the law, and the ways in which the social and political come together, even in benign ways—like this person who is sweeping, cleaning up the parking lot and the surrounding landscape: it makes the rules of life here quite clear. Do you remember the encounter you had with this person?

It was really minimal. I had no particular reason to go to Marion; I just drove through. It was the middle of the day, maybe a little later, and I saw the words that just really stopped me. I thought of the architecture of the building, and I thought of Walker Evans’s photographs of architecture in the South. So I approached and I noticed the man out there and the oversize Cadillac, and I thought, “Okay, obedience, yielding one’s will, subjugation, wealth,” and you know, all of those things were immediate. I asked him if he would pose, and he said sure, and that was it. That was the extent of our interaction. He just continued to sweep, and I set up the camera. My prerogative was to pay homage to Evans, so I kept the building rectilinear. I didn’t want any vanishing points in the architecture, so I did a few view-camera movements to reestablish the orthogonal relationship of the lines. Then I shifted the camera left and right to position the man sweeping and the Cadillac in order to balance them against the neoclassical Greek architecture.

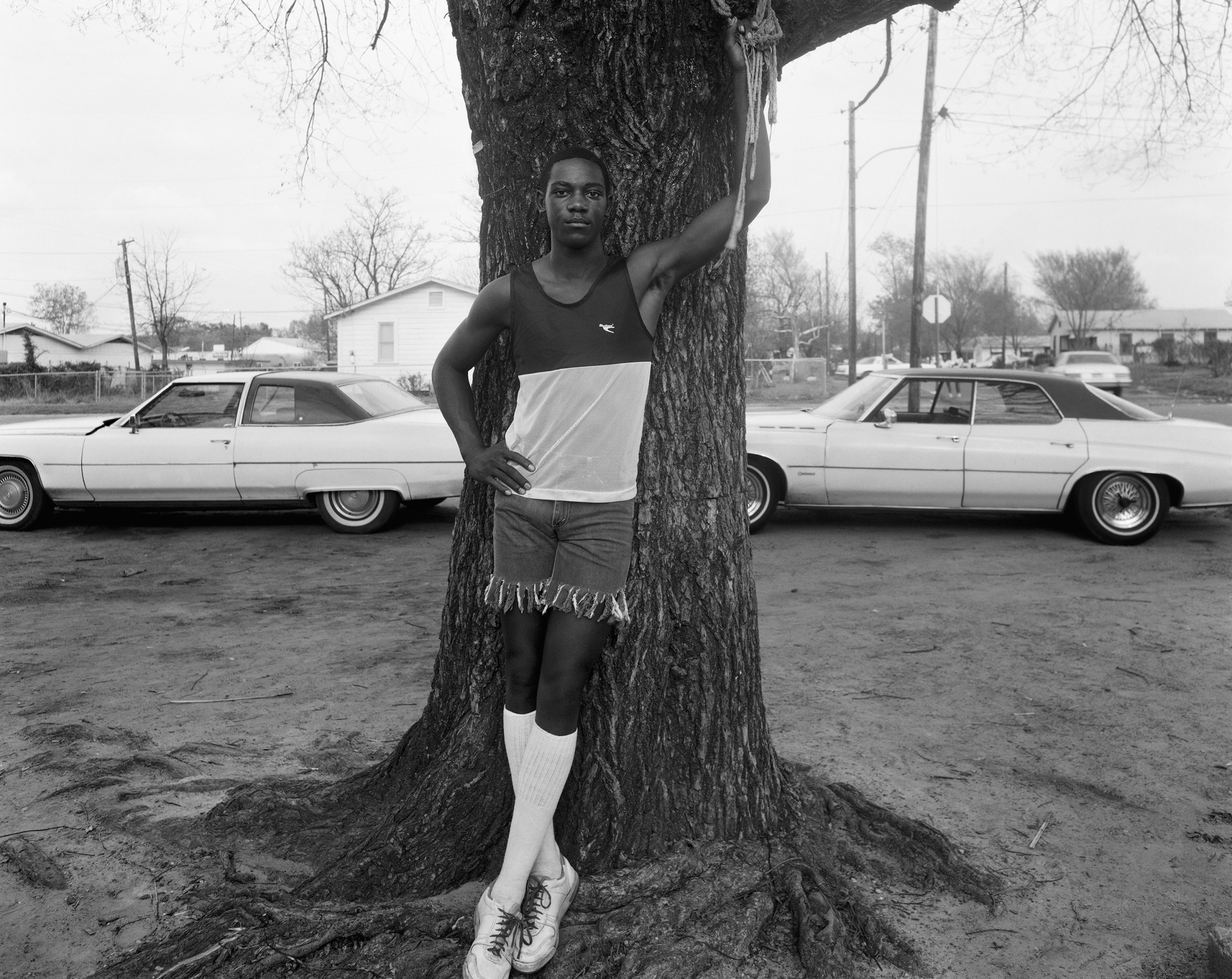

What drew you to the subject of the young man in front of the tree in Untitled (ca. mid 1980s) and this kind of cross-like composition?

In the way that most of my pictures of people start, I saw him and my radar alerted me that he could be good. When I say that, what I mean is: I think this person has the possibility of sustaining interest in a photograph. In a way it is related to fiction writing—establishing a character who can be fleshed out, who could have a more significant role in that portion of a story. I just saw him and thought that his posture, his carriage, his physicality, his musculature, what he was wearing—it was interesting to me. I approached and asked if I could photograph him, and I recall we engaged in some chitchat. I explained who I was and what I was doing and he said, “Sure, fine,” and then he asked, “Well, what do you want me to do?” I just sort of glanced around and said, “Why don’t you lean up against that tree?” because I noticed that there were two cars that were more or less twins, and I thought I could do something.

Then I got underneath the dark cloth and I began to move the camera back and forth and to swing it left and right to figure out how close I wanted to be, how big he should be in the frame. I could have moved in quite close to really draw attention to his facial features, his eyes, the musculature around his shoulders—that would have been another picture. I decided to be at this intermediate distance, and then I got out from underneath the dark cloth and was standing next to the camera, ready to take the picture, and for some reason he reached up. I hadn’t noticed the ropes. And I thought, “Oh my God,” so I said, “Wait a minute!” I had to reinsert the dark slide, which protects the film, to take the film out of the back of the camera, get back under the dark cloth, reopen the lens, and look to make sure that I was including the rope. And I was, so I didn’t have to readjust the camera—it was just by dumb luck that the top edge of the photograph was exactly where it should be. I reinserted the film, closed the shutter, pulled the dark slide, came back out and I asked him to look at the glass of the lens. What that does in a photograph is it re-creates somebody, in conversation, looking you straight in the eye, not looking at your forehead, not looking at your ear, not looking at your nose—direct contact.

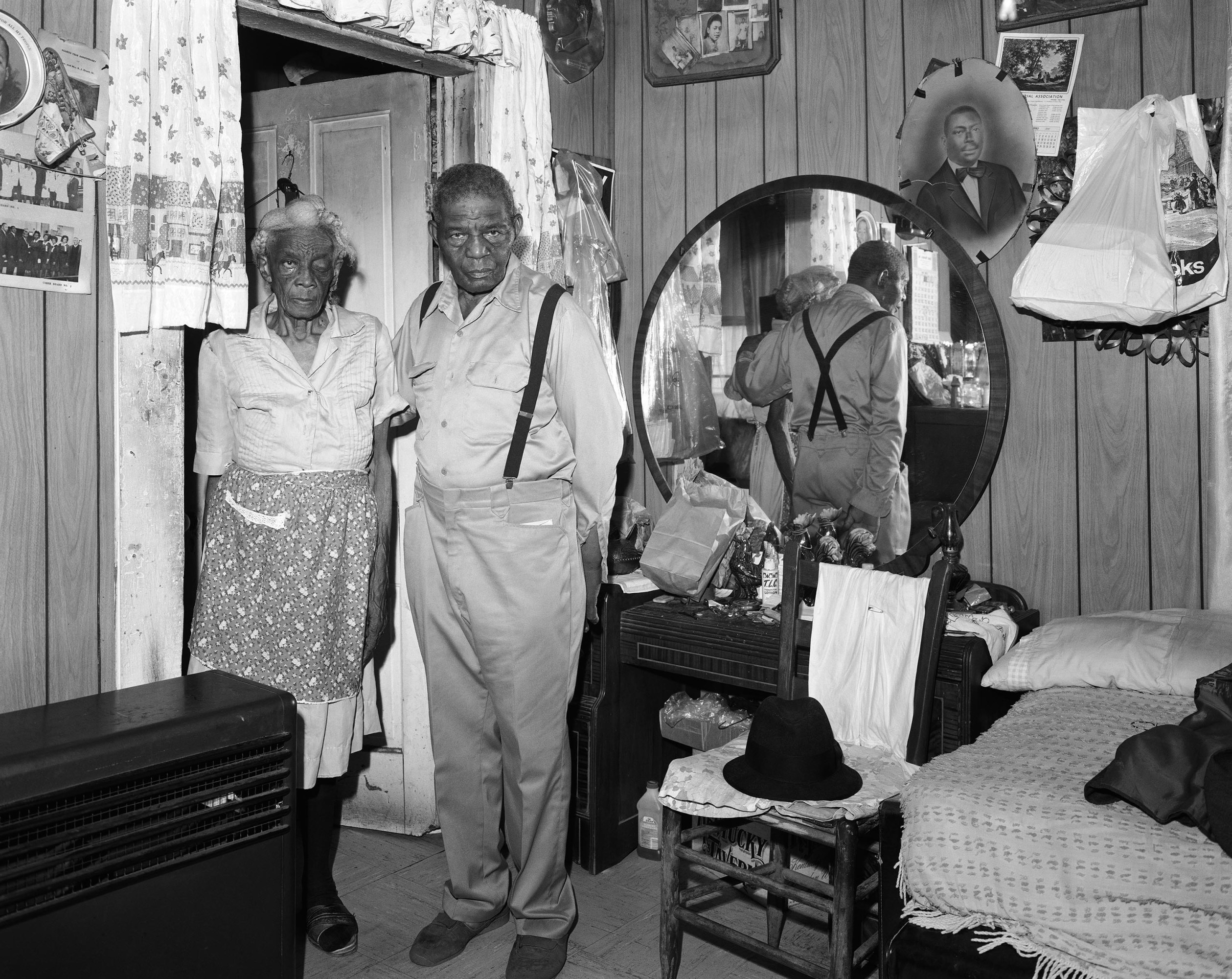

Many of your images attempt to find dignity even in extreme poverty, but all show this great sense of the struggles that accompany such conditions. Yet you also find ways to redirect us from that.

It was always a real bonus for me when I was invited into a household. So much of life occurred in those neutral spaces, but like the previous photograph with the young man in the shorts, the place where most of the initial interaction would occur was in front yards and porches. That is where people would hang out. Now, since everybody has air conditioning, that space of the front yard and porch is not as populated as it once was. You can drive through rows and rows of houses and not see anybody outside. But in the 1980s, in some of the places I went, the poverty was so severe that air conditioning simply was not an option.

I wonder if you could discuss reaching the point where you felt that you had exhausted the form and also had to confront the asymmetry between your life and the life of your subjects.

One thing that I didn’t mention was the photographs I didn’t take. The ones that I didn’t take were the ones that distressed me the most. I don’t remember what year it was, but there was a trip that I embarked on …. I did all my preparation and packing and got in the car; I was in some place in Georgia. I had not stopped—I just drove straight. I saw a man mowing a lawn and he had only one arm. And I reflexively said, “Pull the car over and take a picture!” And when I thought about this reaction of mine, I was mortified. I was ashamed. I felt like the worst person in the world. Why am I delighting in the aftermath of the misfortune that this man had suffered? Why did I think the making of a photograph would justify doing something like this? So I turned around and I went home. That was the only time I ever did that. I didn’t make one picture on this trip. I turned around, and over the hours driving back, I just beat myself up. I kept asking about ambition versus responsibility, ambition versus righteousness. It brought to a head something about the whole enterprise of artmaking that is tainted. The artist is always thinking about fulfilling their ambitions, and when you do that you can’t help but engage in moral compromise. It is inevitable.

Read the full interview with Baldwin Lee in the monograph Baldwin Lee, available through Hunters Point Press.