Photo: Leon Neal (Getty Images)

If you use an Android phone and are (rightfully!) worried about digital privacy, you’ve probably taken care of the basics already. You’ve deleted the snoopiest of the snoopy apps, opted out of tracking whenever possible, and taken all of the other precautions the popular how-to privacy guides have told you to. The bad news—and you might want to sit down for this—is that none of those steps are enough to be fully free of trackers.

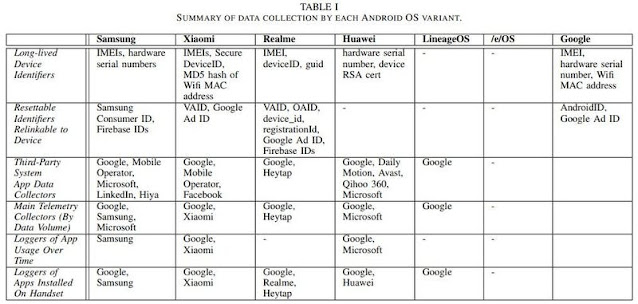

Or at least, that’s the thrust of a new paper from researchers at Trinity College in Dublin who took a look at the data-sharing habits of some popular variants of Android’s OS, including those developed by Samsung, Xiaomi, and Huawei. According to the researchers, “with little configuration” right out of the box and when left sitting idle, these devices would incessantly ping back device data to the OS’s developers and a slew of selected third parties. And what’s worse is that there’s often no way to opt out of this data-pinging, even if users want to.

A lot of the blame here, as the researchers point out, fall on so-called “system apps.” These are apps that come pre-installed by the hardware manufacturer on a certain device in order to offer a certain kind of functionality: a camera or messages app are examples. Android generally packages these apps into what’s known as the device’s “read only memory” (ROM), which means you can’t delete or modify these apps without, well, rooting your device. And until you do, the researchers found they were constantly sending device data back to their parent company and more than a few third parties—even if you never opened the app at all.

Here’s an example: Let’s say you own a Samsung device that happens to be packaged with some Microsoft bloatware pre-installed, including (ugh) LinkedIn. Even though there’s a good chance you’ll never open LinkedIn for any reason, that hard-coded app is constantly pinging back to Microsoft’s servers with details about your device. In this case, it’s so-called “telemetry data,” which includes details like your device’s unique identifier, and the number of Microsoft apps you have installed on your phone. This data also gets shared with any third-party analytics providers these apps might have plugged in, which typically means Google, since Google Analytics is the reigning king of all the analytics tools out there.

As for the hard-coded apps that you might actually open every once in a while, even more data gets sent with every interaction. The researchers caught Samsung Pass, for example, sharing details like timestamps detailing when you were using the app, and for how long, with Google Analytics. Ditto for Samsung’s Game Launcher, and every time you pull up Samsung’s virtual assistant, Bixby.

Samsung isn’t alone here, of course. The Google messaging app that comes pre-installed on phones from Samsung competitor Xiaomi was caught sharing timestamps from every user interaction with Google Analytics, along with logs of every time that user sent a text. Huawei devices were caught doing the same. And on devices where Microsoft’s SwiftKey came pre-installed, logs detailing every time the keyboard was used in another app or elsewhere on the device were shared with Microsoft, instead.

We’ve barely scratched the surface here when it comes to what each app is doing on every device these researchers looked into, which is why you should check out the paper or, better yet, check out our handy guide on spying on Android’s data-sharing practices yourself. But for the most part, you’re going to see data being shared that looks pretty, well, boring: event logs, details about your device’s hardware (like model and screen size), along with some sort of identifier, like a phone’s hardware serial number and mobile ad identifier, or “AdID.”

On their own, none of these data points can identify your phone as uniquely yours, but taken together, they form a unique “fingerprint” that can be used to track your device, even if you try to opt out. The researchers point out that while Android’s advertising ID is technically resettable, the fact that apps are usually getting it bundled with more permanent identifiers means that these apps—and whatever third parties they’re working with—will know who you are anyway. The researchers found this was the case with some of the other resettable IDs offered by Samsung, Xiaomi, Realme, and Huawei.

To its credit, Google does have a few developer rules meant to hinder particularly invasive apps. It tells devs that they can’t connect a device’s unique ad ID with something more persistent (like that device’s IMEI, for example) for any sort of ad-related purpose. And while analytics providers are allowed to do that linking, they can only do it with a user’s “explicit consent.”

“If reset, a new advertising identifier must not be connected to a previous advertising identifier or data derived from a previous advertising identifier without the explicit consent of the user,” Google explains on a separate page detailing these dev policies. “You must abide by a user’s ‘Opt out of Interest-based Advertising’ or ‘Opt out of Ads Personalization’ setting. If a user has enabled this setting, you may not use the advertising identifier for creating user profiles for advertising purposes or for targeting users with personalized advertising.”

It’s worth pointing out that Google puts no rules on whether developers can collect this information, just what they’re allowed to do with it after it’s collected. And because these are pre-installed apps that are often stuck on your phone, the researchers found that they were often allowed to side-step user’s privacy explicit opt-out settings by just… chugging along in the background, regardless of whether or not that user opened them. And with no easy way to delete them, that data collection’s going to keep on happening (and keep on happening) until that phone’s owner either gets creative with rooting or throws their device into the ocean.

Google, when asked about this un-opt-out-able data collection by the folks over at BleepingComputer, responded that this is simply “how modern smartphones work”:

As explained in our Google Play Services Help Center article, this data is essential for core device services such as push notifications and software updates across a diverse ecosystem of devices and software builds. For example, Google Play services uses data on certified Android devices to support core device features. Collection of limited basic information, such as a device’s IMEI, is necessary to deliver critical updates reliably across Android devices and apps.

Which sounds logical and reasonable, but the study itself proves that it’s not the whole story. As part of the study, the team looked into a device outfitted with /e/OS, a privacy-focused open-source operating system that’s been pitched as a “deGoogled” version of Android. This system swaps Android’s baked-in apps—including the Google Play store—with free and open source equivalents that users can access with no Google account required. And wouldn’t you know it, when these devices were left idle, they sent “no information to Google or other third parties,” and “essentially no information” to /e/’s devs themselves.

In other words, this aforementioned tracking hellscape is clearly only inevitable if you feel like Google’s presence on your phones is inevitable, too. Let’s be honest here—it kind of is for most Android users. So what’s a Samsung user to do, besides, y’know, get tracked?

Well, you can get lawmakers to care, for starters. The privacy laws we have on the books today—like GDPR in the EU, and the CCPA in the U.S.—are almost exclusively built to address the way tech companies handle identifiable forms of data, like your name and address. So-called “anonymous” data, like your device’s hardware specs or ad ID, typically falls through the cracks in these laws, even though they can typically be used to identify you regardless. And if we can’t successfully demand an overhaul of our country’s privacy laws, then maybe one of the many massive antitrust suits Google’s staring down right now will eventually get the company to put a cap in some of these invasive practices.