After more than a year of the covid-19 pandemic, millions of people are searching for employment in the United States. AI-powered interview software claims to help employers sift through applications to find the best people for the job. Companies specializing in this technology reported a surge in business during the pandemic.

But as the demand for these technologies increases, so do questions about their accuracy and reliability. In the latest episode of MIT Technology Review’s podcast “In Machines We Trust,” we tested software from two firms specializing in AI job interviews, MyInterview and Curious Thing. And we found variations in the predictions and job-matching scores that raise concerns about what exactly these algorithms are evaluating.

Getting to know you

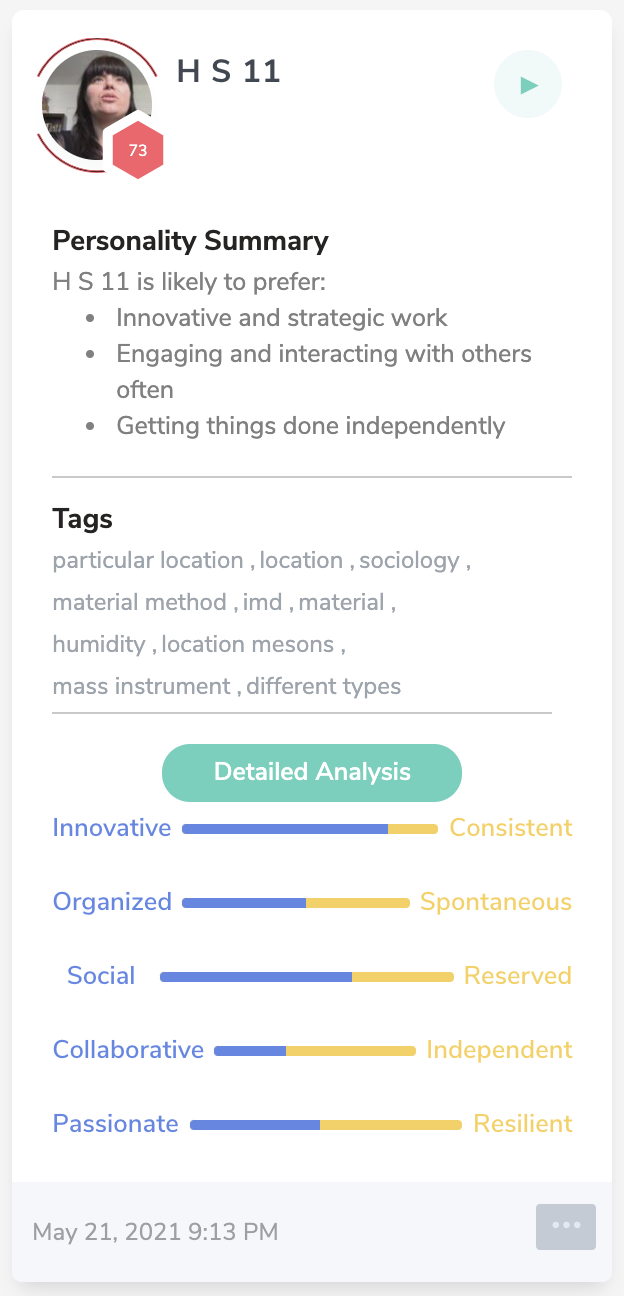

MyInterview measures traits considered in the Big Five Personality Test, a psychometric evaluation often used in the hiring process. These traits include openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability. Curious Thing also measures personality-related traits, but instead of the Big Five, candidates are evaluated on other metrics, like humility and resilience.

The algorithms analyze candidates’ responses to determine personality traits. MyInterview also compiles scores indicating how closely a candidate matches the characteristics identified by hiring managers as ideal for the position.

To complete our tests, we first set up the software. We uploaded a fake job posting for an office administrator/researcher on both MyInterview and Curious Thing. Then we constructed our ideal candidate by choosing personality-related traits when prompted by the system.

On MyInterview, we selected characteristics like attention to detail and ranked them by level of importance. We also selected interview questions, which are displayed on the screen while the candidate records video responses. On Curious Thing, we selected characteristics like humility, adaptability, and resilience.

One of us, Hilke, then applied for the position and completed interviews for the role on both MyInterview and Curious Thing.

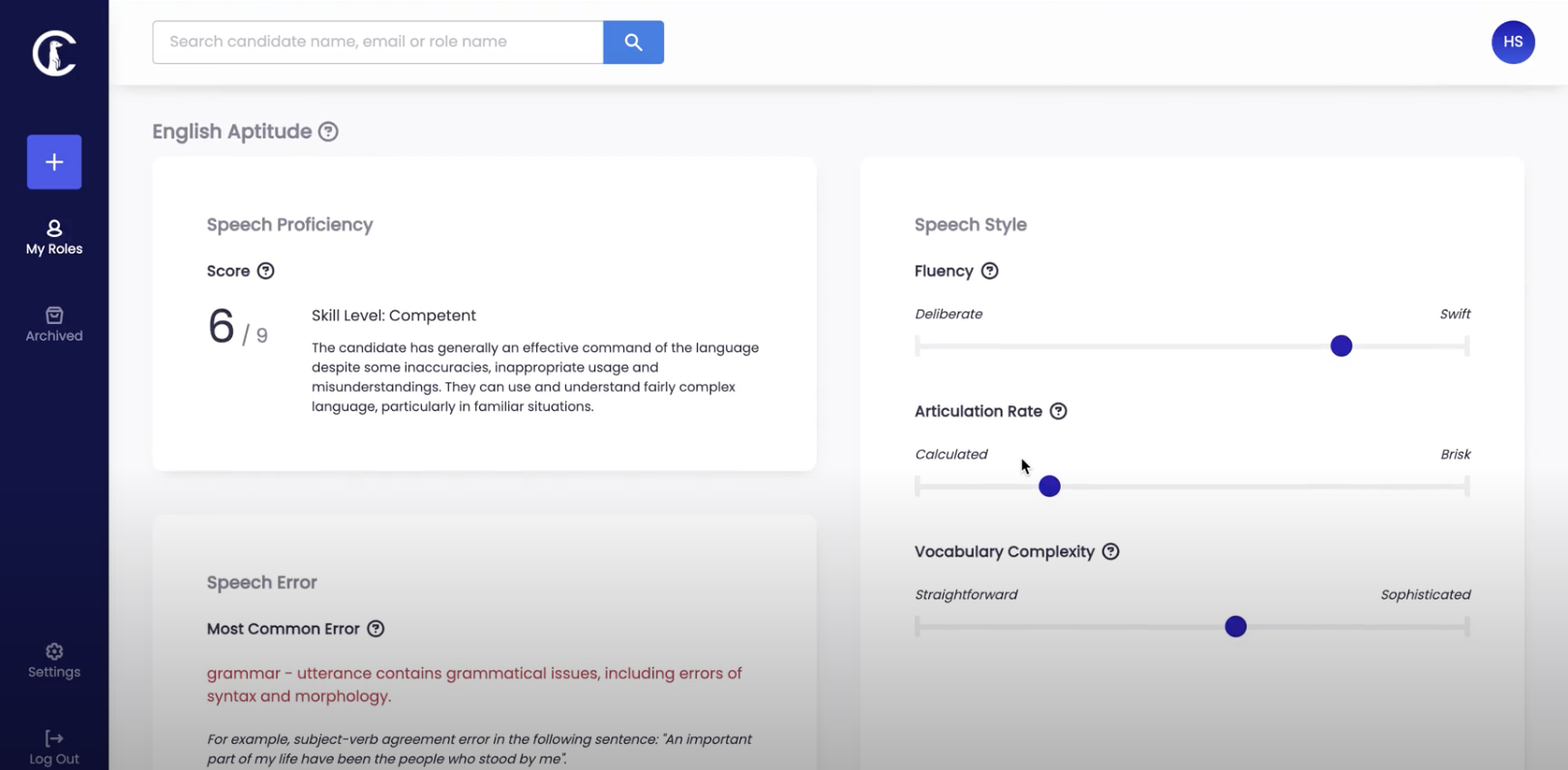

Our candidate completed a phone interview with Curious Thing. She first did a regular job interview and received a 8.5 out of 9 for English competency. In a second try, the automated interviewer asked the same questions, and she responded to each by reading the Wikipedia entry for psychometrics in German.

Yet Curious Thing awarded her a 6 out of 9 for English competency. She completed the interview again and received the same score.

Our candidate turned to MyInterview and repeated the experiment. She read the same Wikipedia entry aloud in German. The algorithm not only returned a personality assessment, but it also predicted our candidate to be a 73% match for the fake job, putting her in the top half of all the applicants we had asked to apply.

MyInterview provides hiring managers with a transcript of their interviews. When we inspected our candidate’s transcript, we found that the system interpreted her German words as English words. But the transcript didn’t make any sense. The first few lines, which correspond to the answer provided above, read:

"So humidity is desk a beat-up. Sociology, does it iron? Mined material nematode adapt. Secure location, mesons the first half gamma their Fortunes in for IMD and fact long on for pass along to Eurasia and Z this particular location mesons."

Mismatched

Instead of scoring our candidate on the content of her answers, the algorithm pulled personality traits from her voice, says Clayton Donnelly, an industrial and organizational psychologist working with MyInterview.

But intonation isn’t a reliable indicator of personality traits, says Fred Oswald, a professor of industrial organizational psychology at Rice University. “We really can’t use intonation as data for hiring,” he says. “That just doesn’t seem fair or reliable or valid.”

Using open-ended questions to determine personality traits also poses significant challenges, even when—or perhaps especially when—that process is automated. That’s why many personality tests, such as the Big Five, give people options from which to choose.

“The bottom-line point is that personality is hard to ferret out in this open-ended sense,” Oswald says. “There are opportunities for AI or algorithms and the way the questions are asked to be more structured and standardized. But I don’t think we’re necessarily there in terms of the data, in terms of the designs that give us the data.”

The cofounder and chief technology officer of Curious Thing, Han Xu, responded to our findings in an email, saying: “This is the very first time that our system is being tested in German, therefore an extremely valuable data point for us to research into and see if it unveils anything in our system.”

The bias paradox

Performance on AI-powered interviews is often not the only metric prospective employers use to evaluate a candidate. And these systems may actually reduce bias and find better candidates than human interviewers do. But many of these tools aren’t independently tested, and the companies that built them are reluctant to share details of how they work, making it difficult for either candidates or employers to know whether the algorithms are accurate or what influence they should have on hiring decisions.

Mark Gray, who works at a Danish property management platform called Proper, started using AI video interviews during his previous human resources role at the electronics company Airtame. He says he originally incorporated the software, produced by a German company called Retorio, into interviews to help reduce the human bias that often develops as hiring managers make small talk with candidates.

While Gray doesn’t base hiring decisions solely on Retorio’s evaluation, which also draws on the Big Five traits, he does take it into account as one of many data points when choosing candidates. “I don’t think it’s a silver bullet for figuring out how to hire the right person,” he says.

Gray’s usual hiring process includes a screening call and a Retorio interview, which he invites most candidates to participate in regardless of the impression they made in the screening. Successful candidates will then advance to a job skills test, followed by a live interview with other members of the team.

“In time, products like Retorio, and Retorio itself—every company should be using it because it just gives you so much insight,” Gray says. “While there are some question marks and controversies in the AI sphere in general, I think the bigger question is, are we a better or worse judge of character?”

Gray acknowledges the criticism surrounding AI interviewing tools. An investigation published in February by Bavarian Public Broadcasting found that Retorio’s algorithm assessed candidates differently when they used different video backgrounds and accessories, like glasses, during the interview.

Retorio’s co-founder and managing director, Christoph Hohenberger, says that while he’s not aware of the specifics behind the journalists’ testing methods, the company doesn’t intend for its software to be the deciding factor when hiring candidates. “We are an assisting tool, and it’s being used in practice also together with human people on the other side. It’s not an automatic filter,” he says.

Still, the stakes are so high for job-seekers attempting to navigate these tools that surely more caution is warranted. For most, after all, securing employment isn’t just about a new challenge or environment—finding a job is crucial to their economic survival.